The Sistine Chapel owes its name to its client, Pope Sixtus IV della Rovere (1471-1484), who wanted to build a new large room on the site where the “Cappella Magna” already stood, a fortified classroom dating back to the Middle Ages, destined to house the papal court meetings. The latter at the time had about 200 members and was composed of a college of 20 cardinals, representatives of religious orders and large families, of the complex of singers, a large number of lay people and servants. The Sistine construction also had to respond to defensive needs against two looming dangers: the Lordship of Florence, run by the Medici family, with whom the Pope was in constant tension, and the Turks of Muhammad II, who in those years threatened the eastern coasts of Italy. Its construction began in 1475, the year of the Jubilee proclaimed by Sixtus IV, and ended in 1483 when, on August 15, the chapel, dedicated to the Assumption of the Virgin, was inaugurated with solemnity by the pope. The project of the architect Baccio Pontelli reused medieval walls up to a third of the height.

According to some scholars, the size of the classroom (40.23 meters long, 13.40 meters wide and 20.70 meters high) would follow the measurements of the great temple of Solomon in Jerusalem, destroyed in 70 AD. by Romans.

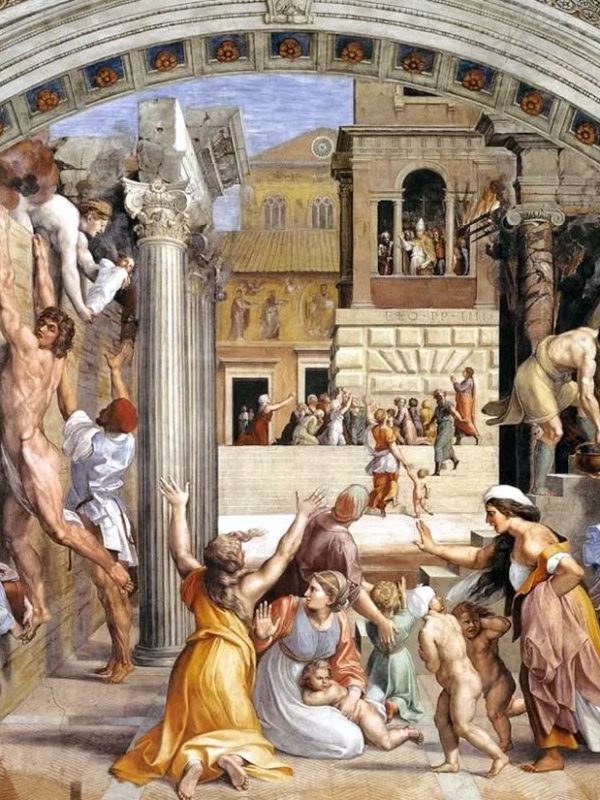

The main entrance to the chapel, which is located on the opposite side of the small entrance which today constitutes the usual access, is preceded by the grandiose Sala Regia, intended for hearings. Arched windows (arched at the top) ensure lighting and a barrel vaulted roof joins the side walls with triangular bezels and sails. The choir on the right side once housed the members of the choir, while the stone seat on three sides of the hall, with the exception of the altar seat, was intended for the papal court. The refined fifteenth-century balustrade topped with candelabra divides the environment reserved for the clergy from that intended for the public: it was set back at the end of the sixteenth century to make the first space larger. The splendid mosaic pavement, which has remained intact today, dates back to the 1400s and was built on medieval models. When the architectural structure was completed in 1481, Pope Sixtus IV called on famous Florentine painters, such as Botticelli, Ghirlandaio, Cosimo Rosselli and Signorelli, as well as Umbrians such as Perugino and Pinturicchio to work in the chapel.

They decorated the side walls, divided into three horizontal bands and vertically punctuated by elegant pilasters. In the lower part, fake damask drapes with the signs of the pontiff were made in fresco; tapestries were hung above them (some, executed by Raphael and his aides in the second decade of the sixteenth century, are now in the room dedicated to him in the Vatican Pinacoteca); in the middle band, the most important, scenes of biblical stories were painted with episodes from the life of Moses and Christ, both conceived as liberators of humanity; in the upper one, at the height of the windows, the portraits of the first popes were made by Sixtus IV, inserted in monochrome niches, to demonstrate the continuity of his mandate with his predecessors.

The ceiling of the chapel, as a famous drawing of the sixteenth century shows today in the Uffizi, was finally decorated until the lunettes with golden stars on a blue background by the painter Pier Matteo d’Amelia.

It was then the turn of Sixtus IV’s nephew, the enterprising Giuliano della Rovere, who became pope with the name of Julius II (1503-1513), to complete the pictorial decorations inside the chapel. As part of the grandiose renewal of the city, he called Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564) to Rome, an artist already famous in Florence and to whom he had previously entrusted other assignments, which he accepted, not without initial controversy, to decorate “fresco” the vault. The work was completed in four years of hard work (from 1508 to 1512) and has as its theme the history of humanity in the period preceding the coming of Christ.

The painting of the wall with the “Last Judgment” was performed instead by the same artist later: from 1536 to 1541, on commission of Pope Paolo III Farnese (1534-1549), who in turn had confirmed the assignment of the previous pope Clement VII (1523-1534). The theme represented this time is the inevitable fate that hangs over all men, whose destiny God is the absolute arbiter.

Biblical Stories of the side walls:

On the walls are represented: on the left, looking at the Judgment, the scenes taken from the Old Testament, with the Stories of Moses, savior of the Jewish people; on the right, those drawn from the New Testament with the Stories of Christ, savior of all humanity. They can therefore be read in parallel. Originally they also included the “Finding of Moses” and the “Nativity of Jesus”, executed on the wall of the current Judgment and then canceled by Michelangelo in 1534. The cycle ends in the wall of the main entrance with the “Dispute for the body of Moses “and the” Resurrection of Christ “, both repainted in the sixteenth century. The writings at the top, recently restored, are called tituli and refer to the contents of the boxes below.

Left wall of the Sistine Chapel

The first painting, the “Journey of Moses to Egypt”, attributed to Perugino, represents the moment when “Moses (…) took his wife and children, made them climb on a donkey and prepared to return to Egypt, bringing in his hand the rod given him by God ” (Exodus 4,20). But during the journey – and here the painting departs from the biblical story – he was stopped by an angel who ordered him to circumcise the second son (right).

The box with the “Prove di Mosè”, work by Botticelli and his workshop, follows. It is one of the most complex, due to the sum of several episodes: on the right, the killing of an Egyptian who had beaten a Jew, the escape to the country of Midian, the meeting with some local girls and the watering of their flock, the apparition of the Lord from a bush of fire (left) and, in the upper center, the apparition of God inviting Moses to take off his shoes in front of him (Exodus 2,11-20 and 3,1-6) . Note the two splendid female figures in the foreground, typically Botticelli.

The “Passage of the Red Sea” is attributed to the painter Biagio d’Antonio (1446-1516). Moses and his people, fleeing Egypt, chased by Pharaoh’s army, manage to cross the Red Sea because God has the waters withdrawn before them; these close over the pursuing Egyptians who, in this way, die together with their horses (Exodus 14,23-30). In the lower left, a woman plays a hymn of thanksgiving to the Lord (Exodus 15.1-20).

The “Delivery of the Tables of the Law”, attributed to Cosimo Rosselli, illustrates the biblical story of the golden calf: Moses had ascended to Mount Sinai to receive the Tables of the Law (Exodus 23.12-15), and the Jews, not seeing him return, they gathered around the priest Aaron; then they collected rings and gold objects and fashioned a calf to be placed on an altar to adore it. When Moses came down from the Mount with the two Tables of the Law, seeing his people who had contravened the prohibition of representing sacred images, he broke them in anger (Exodus 32.1-19).

Botticelli’s “Retribution of Core, Datan and Abiron” refers to the revolt against the Lord, during the journey to the promised land, by the Jews, who complained about the bad living conditions to which they had been forced by Moses; but God punished them by suddenly opening the earth under their feet, which swallowed them up with all their possessions (Numbers 16). Note, against the background of the scene, the Arch of Constantine in Rome.

Also in Signorelli’s “Testament and death of Moses” several episodes are represented: on the right, Moses gives his blessing to the children of Israel (Deuteronomy 33) and, on the left, he gives the rod of command to Joshua. Above: in the center, the angel indicating the promised land and, on the left, the death of Moses.

Right wall of the Sistine Chapel

The “Baptism of Christ“, with episodes taken from the Gospel according to Matthew, is by Perugino. On the left is John’s sermon, which precedes the Baptism of Christ; in the foreground the episode that gives the name to the fresco and on the right the preaching of Jesus to the followers. Note the representation of the Trinity at the center of the work: above the Christ is in fact the dove of the Holy Spirit and, enclosed within a circle, the figure of the Eternal surrounded by angels.

The second box illustrates the “Temptations of Christ” and the “Purification of the leper” by Botticelli, episodes always taken from the Gospel according to Matthew. These are the unsuccessful attempts of Satan against Christ (challenge to transform the stones into loaves, to throw himself from the top of a temple by being saved by angels, offering all the beauties of the world shown to him from a cliff) to push him to worship him (Matthew 4,1-11).

At the center is the purification of a leper according to the Jewish rite.

Note, in the background, the facade of the Santo Spirito Hospital, between the current Via della Conciliazione and the Tiber, built by Pope Sixtus IV.

The “Vocation of the First Apostles” is by Ghirlandaio and illustrates the biblical text (Matthew 4,18-22) to the letter, representing Jesus inviting the fishermen brothers Peter and Andrew (left) to kneel before Him (foreground) and summons Giacomo and Giovanni who are on a boat (slightly at the top right).

The “Sermon on the Mount” (Matthew 5,1-12), attributed to Cosimo Rosselli, represents: on the right the healing of the leper (Matthew 8,1-4); on the left Christ pronouncing the famous “beatitudes”. It correlates with the painting on the opposite wall where Moses receives the Tables of the Law.

The “Handing over of the keys” of the Church by Jesus to Pietro del Perugino is perhaps the most beautiful painting on the walls of the Sistine Chapel. On the background of a perspective pavement, there is a typically Renaissance octagonal temple, flanked by two triumphal arches similar to that of Constantine in Rome, as if to signify the continuity between past and present.

The “L’Ultima Cena” by Cosimo Rosselli and Biagio d’Antonio is characterized by the presence of a semi-octagonal table, which is matched by similar shapes of the walls and ceiling. Judas is portrayed from behind and carries a small devil on his shoulders. In the background, the Oration in the garden, the capture of Jesus.

With its 800 square meters of “a buon fresco” painting, it is Michelangelo’s great masterpiece, one of the most important cycles of world painting. The work was started in May 1508, suffering an interruption of about a year, from September 1510 to August 1511. The chapel was solemnly inaugurated by Julius II on November 1, 1512.

The iconographic program reconnects to the themes painted on the side walls, illustrating humanity’s long wait for the coming of Christ, the prophecies that heralded this event and the genesis of the Creation of the world. All the figures are inserted within a monumental painted architectural structure that overlaps the real vault.

Sistine Chapel Canvas

The reading of the paintings can therefore be divided into three parts.

First part: in the triangular canvas and in the lunettes above the windows are placed the Ancestors of Christ according to the list of the Gospel of St. Matthew (1,1-17). Forced into narrow and shallow spaces, men and women, who represent humanity and the succession of generations, await, with different poses and attitudes, the great event of Revelation: they appear tired, heartbroken, often suffering from inactivity and exasperated for the very slow passage of time that separates them from the birth of Christ. Some of these paintings show an extraordinary technical ability, such as the figure of Mathan (on the wall of the ancient entrance) or that of Iosaphat (in the center of the wall with the Stories of Christ), frescoed quickly with quick brush strokes and with very colors fluids.

The four corner canvas depict episodes that allude to the salvation of the people of Israel. Starting from the side of the ancient entrance you will find:

– on the right, “Judith and Holofernes”: the moment in which the young Jewish girl, drunk and killed the Assyrian general Holofernes, who had been ordered by the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar to move against the Israeli army, is shown here to his handmaid (Judith 13.8-10);

– on the left, the canvas with the episode of “David and Goliath”: during the war between Jews and Philistines, the young David had the courage to fight against the giant Goliath, who had sworn that he would reduce the Jewish people into slavery, if he managed to defeat the Jewish army (1 Samuel 17.41-51).

Towards the wall of Judgment, the sails represent:

– on the right, the “Bronze Serpent”, to recall the biblical episode in which the Lord sent snakes against the Israelites; in fact, marching towards the promised land, discouraged by the efforts, they had aroused against them his anger and that of Moses (Numbers 21,8); repenting of his behavior, the people marching in the desert were forgiven: God therefore told Moses to fashion a bronze snake; whoever, after being bitten by a snake, had looked at him, would have been saved;

– on the left, the “Punishment of Aman”, an episode taken from the book of Esther, which recalls the death of a young vizier named Aman; the latter had enacted an edict against the Jews, according to which anyone who had not bowed before the king would have been killed. But Esther, wife of a Persian king, managed to withdraw the decree, thus saving the people of Israel, and to send the vizier Aman to death. The canvas are surmounted by bronze nudes in symmetrical poses and by bucrani (ox skulls), a classic ornamental motif that alludes to sacrificial rituals.

Second part: in the outer belt, seated on mighty thrones delimited by naked monochrome putti on plinths, there are the splendid figures of the seven biblical Prophets and the five pagan Sibyls: they have in common having announced the coming of Christ. The various characters are accompanied, in the background, by angels or cherubs who emphasize their function. Everyone is taken up in the act of reading a book or unrolling a parchment, engaged in an extraordinary spiritual and physical effort at the same time. Among the most beautiful figures the Delphic Sibyl, and the prophets Ezekiel and Jonah: the latter is represented next to the fish within which he remained for three days, the same time of stay of Christ in the tomb before the Resurrection.

Third part: in the central rectangles there are nine scenes, four larger and five smaller, taken from the book of Genesis, with three episodes concerning the creation of the world, three the story of Adam and three the events of Noah. Michelangelo began to paint the vault from these last episodes, reserving, perhaps intentionally, for a second time the scenes in which the Creator appears.

The three creations begin with the box of “Separation of light from darkness” (Genesis 1,3-4), characterized by the figure of the Creator who, wrapped in a pink cloth, occupies almost all the space available in a very perspective view. complex. The painting was executed by Michelangelo in one day of work, according to what recent studies carried out after cleaning have shown.

It is followed by the “Creation of the stars and plants“, a scene divided into two asymmetrical parts, in each of which the figure of the Lord appears: on the right, he is taken frontally, with a gesture that seems to overwhelm everything, while creating the circles of the shining sun and the palest moon; on the left, with a bold vision of the shoulders, He is depicted giving rise to the world of plants (Genesis 1,12-16).

The third box is the “Separation of the earth from the waters” (Genesis 1,7-9), which is also very suggestive for a perspective vision never attempted before.

And then here is the famous “Creation of Adam”, a composition whose fulcrum, slightly shifted to the left, is made up of the two hands of the protagonists who have just loosened up from the squeeze. The body of Adam is splendid. The figure of God is wrapped in a pink cloth and flanked by wingless angels and an astonished expression. It is interesting to note that, in reality, the two figures of the Creator and Adam were obtained from the same preparatory cartoon almost to support the biblical statement according to which “God created man in his image” (Genesis 1:27).

Then follows the “Creation of Eve”. Note how in Michelangelo’s painting the first woman was born from the living rock and not from the rib of Adam according to the biblical story.

The sixth compartment is occupied by the “Original Sin” (on the left) and the “Expulsion from the Earthly Paradise” (on the right), episodes divided by the tree of evil on whose trunk the snake wraps itself and behind which appears, at the top, the ‘Archangel Gabriel. The tree, in a slightly asymmetrical position with respect to the center of the composition, is a gap between a lush landscape and an arid nature, expressions of the different determination of the human condition. Even the bodies of the progenitors appear different after sin, almost aged, demonstrating how, for Michelangelo, the physical aspect is also an expression of inner spirituality.

The seventh scene, the “Sacrifice of Noah”, concerns the thanks of the Patriarch to the Lord after the flood. In the foreground, the offering of the bowels of a ram: “Then Noah erected an altar to the Lord, took every species of pure animals and every species of pure birds and offered them as a holocaust on the altar” (Genesis 8,20).

The “Universal Flood”, in the eighth box, is freely taken from chapters 7 and 8 of Genesis. On the right there is a tent under which terrified refugees take refuge; in the center, the few survivors are brought to safety by Noah who, with a boat, starts them towards the ark, a symbol of the Church, depicted at the top left. In the foreground, set on a diagonal, the salvation is described: after the flood and the withdrawal of the waters, the survivors land on the earth carrying with them the few material goods saved. The scene is populated by as many as 60 figures that stand out against a light background, in a deep landscape. This was probably the first episode to be performed by Michelangelo: from then on the artist will prefer larger images, with always daring and compositionally complex glimpses. A burst in 1797 in the Castel Sant’Angelo dust deposit unfortunately caused a part of the sky to collapse where, as evidenced by 16th century prints, lightning was represented.

Follows, in the ninth box, the one closest to the original entrance to the Chapel, the “Drunkenness of Noah” (Genesis 9,20-23), which represents the resumption of life and agricultural activity on earth. “Noah began to be a farmer and planted a vineyard; he drank the wine, got drunk and slept naked in the middle of his tent. Cam, father of Canaan, saw the nakedness of his father and ran outside to tell his brothers.

But Sem and Jafet took a cloak, put it on their shoulders, and walking backwards, they covered their father’s nakedness; and since they had their faces turned back they did not see his nakedness.”

The scenes of Genesis are surrounded by the Ignudi, extraordinary male figures, with a powerful build, which perhaps allude to the beauty of man, created in the image and likeness of God: seated on marble cubes, with “screwed” poses, they support festoons or they tend ribbons to which large bronze medallions are tied with scenes still taken from the Old Testament. Their compositional function is noteworthy, because they interrupt the continuity of the members and link the various panels of Genesis. It has been observed that “their presence on each of the four projections serves to frame the minor scenes in an apparently more spontaneous way, and therefore performs an essential task in the alternating rhythm of the nine compartments” (R. Pane, 1964). This essential function can be better understood by observing, between the first and the second scene, the arch that was deprived of the painting due to the fall in 1797 of a part of the fresco.

From the pictorial point of view, some important details are still to be noted: the enlargement of the figures of the Ignudi and the Redeemer in the direction of the altar; the diversified use of colors, spread more densely in Noah’s Stories and more quickly in the last scenes. Finally, the foreground images are focused with clear and precise contours, while the more distant ones behind them are treated with more fluid brush strokes and shaded contours according to the technique that Michelangelo had probably learned from his contemporary Leonardo.

The Sistine Chapel continues with an element that seems to be totally estranged from the vault, due to the particular organizational scheme, the general gigantism of the figures and the absolute dynamism:

The Last Judgement. Here the mystical concept is expressed by an exceptional dynamism, by absolute vitality and carnality.